The slogans raised by the “Green Politics” to combat the global environmental crisis they are increasingly visible to the common of all of us. Phrases such as “ecological conversion”, “reduction of climate footprint”, “Ecofriendly”, are some of those used by large companies, national and international, to disguise their extractivism.

The current paradigm that marks the way in which natural common goods are exploited puts their sustainability in check. Not only does it directly affect the integrity of ecosystems, but it also greatly harms the quality of life of society, mainly of the communities that live in the vicinity of the sources of extraction of these resources.

And coveted ore worldwide that has been drawing the attention of various economic groups is the lithium. This is because it is one of the main raw materials used in the battery production. With the rise of energy “ecological conversion”, from the shift from fossil fuels to devices that store energy in batteries, lithium mining is increasingly legitimized. But heWhat is lost in this discourse is the other side, which it leaves in the territories where its extraction is located. We are talking about its environmental impact and the impact on communities attributed, mainly, to the large volumes of water used for extraction, in areas with a high water deficit.

Lithium in the Puna region is obtained by a method known as “evaporitic”, whereby evaporating the water from the basin, the lithium salt (lithium carbonate) is decanted. It is denounced that this form of extraction leads not only to the degradation of these ecosystems, but also to the lack of availability of water for the communities that live in the area. In the case of Jujuy, for more than ten years the communities have been claiming and fighting for this reason in the Salinas Grandes region.

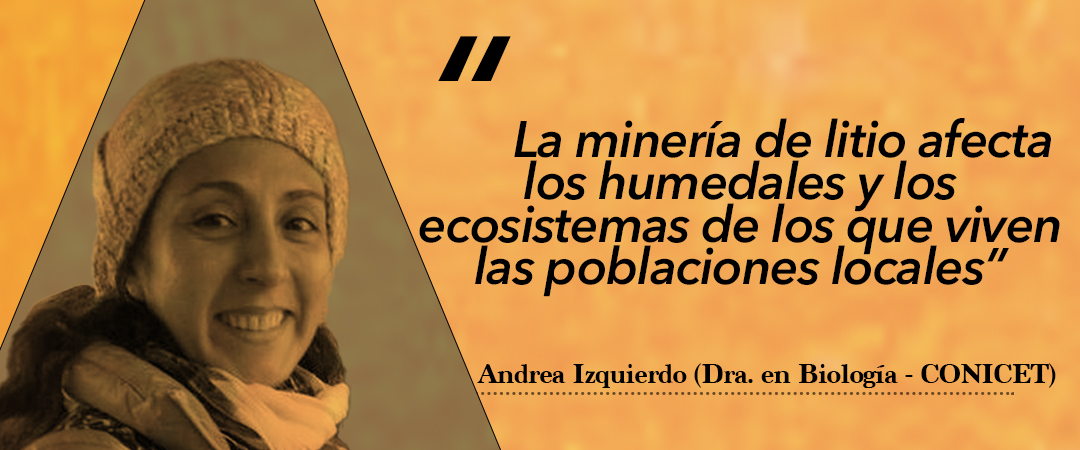

From The Left Daily we interviewed Dr. Andrea Izquierdo, to know the Current situation of the high Andean wetlands in the provinces of Jujuy, Salta and Catamarca. Andrea is a biologist and CONICET researcher. She is dedicated to the study of wetland ecosystems in Argentina, with a socio-ecological approach, looking for possible guidelines for their conservation and their sustainable use.

In what places did you work? What is the research you are conducting about?

I used to work at the Institute of Regional Ecology of the UNT and CONICET and three years ago I moved to IMBIV CONICET – National University of Córdoba. I have been studying the ecology of high Andean wetlands in the Argentine Puna for twelve years.

The project was born out of interest in these systems that seemed very relevant to the ecology of the place and life in general in the place as landscape units with a very small surface area, but which support all life, both wild and human, in an ecoregion. that water is a limited resource.

The first step of the project was to carry out descriptive studies because not much was known about the extent, location and location, so we made the first regional map of the wetlands of the entire ecoregion from Jujuy to San Juan, focused on Las Vegas. We began to identify the importance of other types of wetlands, such as lakes and lagoons and salt flats, because at that time the focus was already beginning to be on the litiferous issue.

We began to do many studies on biodiversity in Las Vegas, mainly on hydrology issues and other ecosystem services that these ecosystems provide, such as carbon sequestration in the soil. Currently, from going to the countryside so much and being with people and so on, I am doing more social issues, such as surveys on local knowledge about the impact of climate change.

I also work very closely with communities or government actors, especially decision makers who are generally consulting information on these ecosystems.

What consequences and/or impacts does lithium extraction have on society and the environment?

We are beginning to notice the growing interest in lithium and changes in communities, roads, traffic, etc. With interest, concern about the impact that this brought about began to grow and, above all, with this discourse that this was the green energy transition or the solution to the problem of fossil fuels, without considering these potential impacts in the balance.

Basically The impacts that lithium mining can have are changes in the hydrological system of the region and atmospheric changeschanges in the whole local vegetation dynamics, etc. Mainly what happens is that these are endorheic basins, that is, all the water circulates within the basins, so what falls by precipitation, snow or rain infiltrates and feeds the underground water tables. That nappa is what sustains these special wetlands, when it is very close to the surface or appears on the surface, it allows the growth of very particular plants that work as if they were sponges, they retain water and keep it on the surface, and at very slow flow rates, then you have a place where vegetation grows and there is also surface water. For this reason, these places provide fresh water, pasture and fodder for wild species and also for the domestic livestock of the inhabitants. The groundwater is connected to the salt flat, which is where the entire endorheic basin flows into.

There are studies carried out in lithium mines in Chile that show that pumping brine in the salt flat affects the water pressure of this systemsince the water table begins to go down in depth, affecting the systems that surround the salt flat, drying up wetlands, and degrading these ecosystems. Therefore it affects the populations that live on it.

To that is added the use of fresh water made by the mines, that is, they compete for very limited resources. Although the system of the pools where it evaporates, they do not use a large amount of fresh water during the production process, they do use water for their camps, to clean the pipes. There is a percentage of fresh water that is used in the processes. In general, it is also the case that many of these companies obtain fresh water from the groundwater table, again, by pumping water and changing the groundwater balance or drawing from rivers. That is why many of the communities denounce and show that the water flow of their rivers is decreasing in the presence of mining.

Then, the other thing is the microenvironmental changes, the microclimate of the places where the companies are is modified. Other environmental impacts that are always associated with mining are the issue of atmospheric dust, a greater amount of traffic, changes in the dynamics of the common cultural-social life of the area.

Another big problem is that due to the same system, the regulations that we have, for mining permits, monitoring and inspection, do not consider the accumulated impacts, that is, for companies that are in the same basin, each one makes its own balance, but they never add up. Neither the companies nor the enforcement authority consider that these impacts accumulate over time.

All this takes place in a context of climate change, with research showing that there is already a process of aridization in the area.

What is the importance of wetland conservation?

Wetlands in general, worldwide, are the ecosystems most affected and pressured by anthropic (human) activity. In these arid places like the Puna, they are even more important. Las vegas, which are the wetlands that provide fresh water to the entire system, are 1% of the total area of that ecoregion, with that minimum extension they are the vital resource for all biodiversity and for all human populations in the area . In addition, the high Andean wetlands, like all mountain regions in the world, are the most vulnerable to climate change.

What is the policy taken at the government level?

There is a national scale and provincial scales, which are litiferous issues, which has a lot to do with it because the provinces have autonomy over their resources.

For me there is a great conflict of interest in the management of the regulations, because the same mining secretariats of the provinces, which are the groups whose objective is to promote mining, are the same ones that evaluate the permits and supervise these companies. So the conflict of interest is great, which greatly limits decision-making to set limits or regulate that activity in a more efficient way.

On the other hand, we have a limitation in the capacity of this technical staff, because they are generally small secretariats, with few staff, and therefore have little interdisciplinary capacity. These shortcomings make it very difficult to modify decision-making and regulate this activity efficiently.

What I see as increasingly difficult to transcend is the lack of possibility that all the relevant actors have for a dialogue that allows us an enriching debate. I don’t see the ability of either actor to really listen to what the other actor is saying. Each one in his position trying to convince the other actor that “if they understand what I am saying or proposing they will realize that they are wrong” and I see that in all the actors, let’s not even talk about consensus.

What would be a comprehensive solution to the problem for you?

The first is to recognize the value and right of local communities in their territory, the decision in the territory must be subject to what the communities want. In this it is also difficult to reach a position of agreement, because even the communities themselves have their own internal conflicts regarding these positions, so first of all for me it is to assume, recognize and respect that the communities have their right to make decisions. their territories and if a community says “no to mining” we need to be able to understand that this “no” is respectable.

It happens that within this model it is difficult to think about that because the economic interest is so great that it ends up being a very unequal fight. I think that the first thing we should do is change the paradigm we are in, although I see that as more difficult.

There are researchers working on replacing the evaporitic technique with others. Perhaps there would be a more possible dialogue with the communities?

Maybe it is possible, but in other cases not. Lithium mining has two main aspects: first, it is “to do it or not to do it”, and that is for the communities to decide. If it is done, then define where and how it is done and there comes all the technological development, science and technology capacity of how to do it better and a whole government management supervising and regulating that it is done in a certain way.

It is necessary to capitalize on the information generated in the environmental impact collections and others to better assess these impacts, but we do not have that much access either, it is not so easy to obtain.

Source: www.laizquierdadiario.com