The rise in interest rates has allowed banks to earn more money than ever, despite having less activity. The mortgage market is showing signs of slowing down and deposits are reducing. However, the sector’s income has not stopped growing until September, providing the highest profit in history and being on the verge of surpassing last year’s record with three months remaining. And all this, in the middle of the debate on making the bank tax permanent as PSOE and Sumar have agreed in the coalition Government’s commitment.

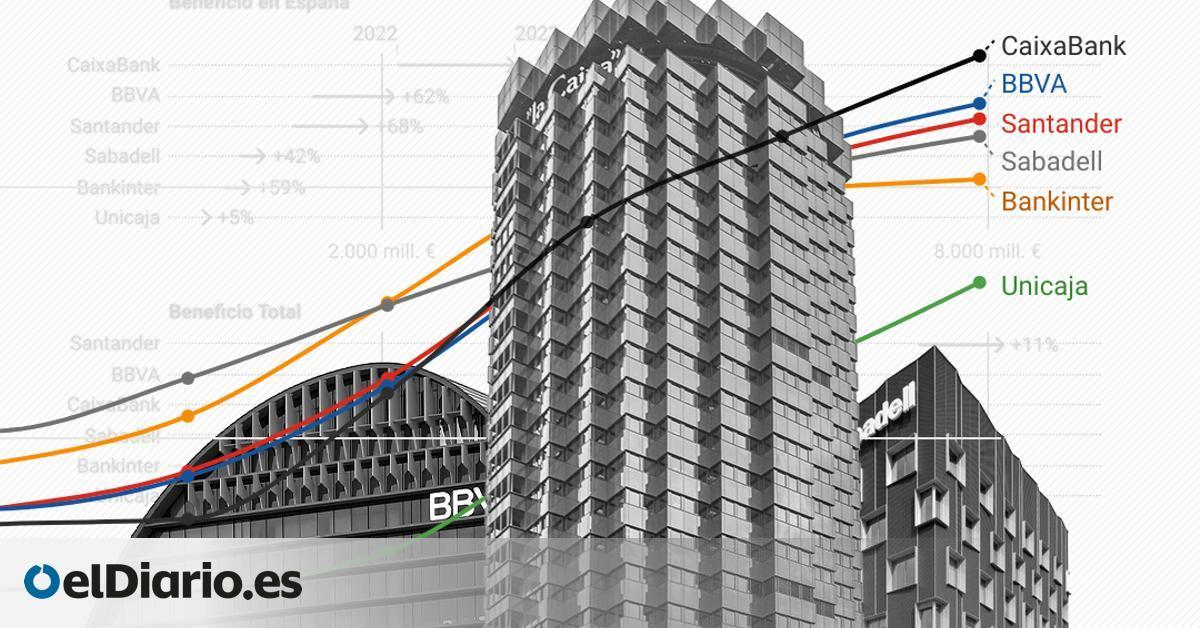

As the months go by, banks are receiving more and more profits from the rise in interest rates. This is shown by the data presented by the six large entities in recent weeks. Together they added a profit of more than 19.7 billion, with a growth of 24% and already reaching record profits for all of 2022 (20.8 billion) with three months left to end the year.

In October, the Euribor reached a new record since 2008 and thousands of households continue to see their monthly payment continue to grow. This trend will continue for at least a few months. The Bank of Spain calculated this week that at least 30% of households are still awaiting updates that will increase the cost of their loans by more than one point until June next year.

As households have seen their mortgages become more expensive, banks have improved their income. The main magnitude of an entity’s turnover is the interest margin, which is the difference between what they earn from their activity and what they have to pay in interest. The rate increase has triggered a magnitude that was barely growing during the years prior to 2022. Taking into account only the business in Spain, the six main banks have increased this source of income by more than 50%, up to 20.6 billion.

But beyond the big figures, exploring the accounts of the main banks serves to find some details that show the extraordinary situation of the results. A magnitude that has gained relevance in recent months is known as customer margin. This is the difference between the average interest rate that the bank receives for lending money and the rate it pays for deposits.

This margin has not stopped growing since the Euribor began to rise at the beginning of 2022 with the problems generated by the war in Ukraine and in view of the forecast of the ECB’s rate hike, which arrived in the summer of that year. Except in Unicaja, this margin has exceeded 3% in large entities, doubling in less than two years in some cases.

This occurs because the transfer of the rate increase to mortgages has been quite automatic, while the banks have for the moment closed the door to payment for customer deposits. Spain is one of the European countries that, on average, pays consumers the least for their money and the sector does not expect this to change in the short term. Sabadell or CaixaBank have made their first moves, but very timid and not in the sense of a typical deposit.

In practically all entities, the yield on loans quadruples what they pay for deposits. For example, the yield on Santander loans in Spain is 4.17%, compared to a deposit expense of 0.9%. Similar figures in CaixaBank, with 4.23% compared to 0.71% or in BBVA, with 4.01% compared to 0.68% The policy of keeping the belt tight at this cost is turning out to be very profitable for the banks.

It is the small and foreign banks that are betting more on capturing customer deposits. The big ones, however, do not see it as a priority and have cooled down during the results presentations that this cost is going to rise soon. “It is an issue of competition and liquidity. In the short term I do not foresee a significant increase in deposits in Spain,” said Onur Genç, CEO of BBVA. The same body whose decisions have caused the increase in mortgage costs, the ECB, was in charge of showering the banks with liquidity in previous years, so much that despite having turned off the tap it has meant that they now have no incentive to pay. for having clients’ money.

Therefore, banking results show that income is growing, margins are increasing and profits are soaring. And, in fact, they do it with less activity. The same accounts draw a reality of the sector in Spain that differs with the evolution of commercial intensity. Fewer loans are signed, the debt management of households and companies is reduced and the volume of deposits on the banks’ balance sheets is substantially cut.

Specifically, the six large banks have seen 36.7 billion euros in deposits disappear from their balance sheets compared to September of last year. This is due to movements such as the reduction in the savings pools of households and companies generated during the pandemic or that, according to banks, is being directed to savings products outside their balance sheets, such as investment funds. Regarding credits, 42.8 billion live loans managed have disappeared. As explained in the sector, it is due to early loan repayments and the brake on the granting of new financing.

Mortgage market data show a downward trend, with percentages of decline exceeding 20% in the granting of new loans. This is the banks’ main credit business, but the rise in interest rates, the increase in the cost of loans and the increase in prices is causing households to demand less credit after years of mortgage boom. In fact, so far this year, more mortgages have been canceled than have been signed. Of course, the debt that is still alive and the new loans are more profitable for the banks, so their income not only does not suffer but increases.

Confrontation between banking and Government

With these data on the table, the confrontation between the bank and the coalition government has once again become evident. The banks have already recorded in their balance sheets the impact of the temporary tax that they have to pay this year, the first of the two that will be in force for now. However, this extraordinary impact has not prevented profit growth from being historic. The Bank of Spain itself, originally critical of this tax like the ECB, concluded in its Financial Stability Report presented this week that the banks “more than compensated” the impact of the tax with the increase in income.

“Of course there is room for financial and energy entities, which are presenting multimillion-dollar results these days, to make a greater tax contribution than what they currently make,” said acting vice president Nadia Calviño in a recent interview based on the presentations. of results. “Maintaining the bank tax and ensuring that it contributes to the common good is one of the great achievements of the government agreement,” added Yolanda Díaz, second vice president and leader of Sumar, on social networks.

The Government is committed to maintaining the tax, without specifying whether changes will be introduced. The sector, however, maintains its negative. Of course, modifying your answer in a certain way. If at the beginning of the year it was proposed that the new tax would stop credit and would be passed on to clients, now with the experience of the first year they point out that this omen is for the future and not in the short term. “The impact has more to do with the long term,” said Genç, from BBVA.

Now they have added ideas such as that it “stigmatizes” banking, as Héctor Grisi, from Santander, proposed, or that “there is differential and negative treatment against banks”, as Gonzalo Gortázar, from CaixaBank, pointed out. However, they maintain their denial of the existence of extraordinary profits that should be taxed. “It is a moderate profitability,” said Gortázar. And the banks maintain that it is not an increase in interest rates but rather a “normalization.” That is to say, the current situation, with rates at maximums of more than 20 years, is normal and not the situation of recent years. In fact, they consider that there would still have to be a higher profitability for it to be confirmed in the stock market value of their shares.

Source: www.eldiario.es