“The Gag Law and the Reform of the Criminal Code have been approved by the PP roller. We will repeal them when we govern.” This was expressed on March 26, 2015, the then opposition leader, Pedro Sánchez. One of the most representative norms of the mandate of the PP of Mariano Rajoy celebrates a decade. The promised repeal of the law will not be carried out at 100%, although the PSOE and part of its partners have achieved, after years of disagreements, an agreement to reform its most harmful aspects, whose approval is pending in Congress.

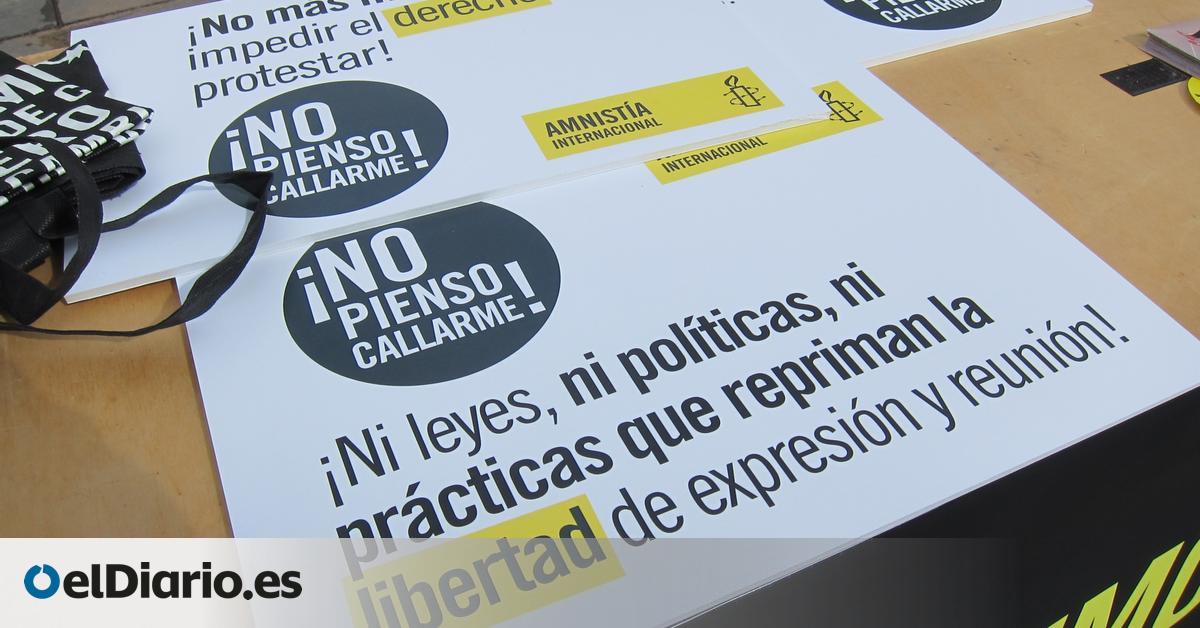

“The law has had devastating effects on civil liberties, especially the right to protest,” says Cèlia Carbonell, a member of the Irídia center. “It is incomprehensible that the law has not yet been repealed or a deep reform has been carried out,” verifies the Professor of Criminal Law of the Oberta Universitat de Catalunya (UOC), Josep Maria Tamarit.

The experience of this decade, highlights the professor, has shown “a rather arbitrary use of police powers, with a wide margin of tolerance towards certain behaviors, without being able to foresee when they will make use of their powers and why.” “And with Covid, unjustified use of the law was made to apply excessive control to the population,” says Tamarit.

The use of the standard during the alarm status and the subsequent unwinding of the COVID has made, as shown by the data of the Ministry of Interior analyzed by Eldiario.es, 2020 was the record year in collection of fines for the ‘Gag Law’, with a total of 252 million euros.

The following year with greater collection was 2023, with 175 million euros, while in the remaining years, the fines are around 150 million annually. Between 2016 and 2023 (last year with available figures), the sanctions amounted to a value of 1,250 million euros. The number of fines does not present large variations both under governments of the PP and the PSOE and its partners to the left.

For reasons of sanction, three articles represent 90% of the fines of the ‘Gag Law’: the most repeated was the consumption of drugs in the street, which has brought fines worth 803 million euros. They are followed by resistance or disobedience to authority (246 million) and the exhibition of prohibited weapons (104 million euros).

“There are aspects of the law, such as weapons control, which have a meaning and should be a priority,” says Tamarit, which also recalls that the norm was endorsed almost entirely by the Constitutional Court. However, the professor also denounces that the rule has enshrined more serious administrative sanctions “and with less guarantees” than those that the courts previously imposed with the old offenses.

“The sanctions provided for in the law are disproportionate: up to 600,000 euros can reach,” recalls Tamarit, adding that infractions “are not sufficiently defined, a concept as indeterminate and dangerous as ‘social alarm’ (or ‘citizen security’ itself) is used and acts whose impact on security is not clear if we understand it in a restrictive sense, as mere consumption of a restrictive sense, drugs ”.

One of the most controversial aspects of the norm is the administrative sanction for disrespecting the agents of the authority, non -existent in other officials of officials. This has behaved from both anonymous retirees who protested a racist performance and Pulitzer Awards and Javier Bauluz, fined by the Gag Law while photographing the arrival of migrants to the Canary Islands.

The political path for reform

During these ten years, leftist groups and nationalist forces have tried up to four times to shape a text that modifies the most harmful aspects of the norm. The attempt that came the most occurred during the past legislature, from a text of the PNV, but then the tensions between the PSOE and independence parties such as ERC and EH Bildu disrupt the negotiations.

These conversations collided in four points: the use of rubber balls – which does not regulate this norm -, hot returns, fines for disobedience and lack of respect for authority. ERC and EH Bildu demanded the elimination of those four points, the most “harmful”, according to their arguments, and the PSOE dismissed those demands that it considered “excuses.”

In October last year, the government reached with EH Bildu an agreement to reform the law. That text spoke of replacing rubber balls with less harmful material and includes a provision so that within six months a modification is addressed in the Foreigner Law. This agreement served to also bring ERC closer to the agreement and facilitated its taking into consideration.

The parties now debate on that agreement as the basis for the reform that everyone expects to be approved by Congress before the session end. For Carbonell, from the Irídia center, that pact is “an opportunity that presents advances”, although it is “insufficient for the total guarantee of rights and freedoms”, and warns that human rights organizations will press so that changes in the law “are a guarantee and not a repression of rights and freedoms.”

On July 1, date on the calendar

Parliamentary sources confirm that there have been some meetings between the groups to begin negotiating a text from the amendments they recorded at the end of last year. These meetings have occurred bilaterally among some of the groups that make up the investiture block, although the general sensation is that things have barely moved for now.

All parties have in the head as a limit on July 1, when ten years of the date on which the law officially entered into force. Sources of adding call on responsibility to other groups so as not to allow that “ignominious date” to be reached without agreement to repeal the law and ask some formations not to put their “partisan interests above the generals before.” Moreover, given the possibility that this legislature is the last opportunity to address this reform before the perspective of a majority of rights in the next elections.

The matches that have put more fight to the text in their amendments are Podemos, Junts and the BNG. Ione Belarra’s party gave its support in October to the taking into consideration of the proposal of law, but has claimed that the prohibition of rubber balls and hot returns is effective. In one of the amendments, to which this newspaper had access, they include an express prohibition of rubber bullets “or any other analogous instrument that can produce for serious injuries, losses, uselessness or deformity of organs or members, loss of a sense or even death.”

Junts and BNG also registered amendments that go along the same lines. Catalan independentistas establish that on December 31 of this year “the total prohibition” of these projectiles is effective and a new model is established that “in any case must guarantee the availability of robust tools that allow a range of differentiated tactical options.”

The law that has begun to process Congress collects however a good part of the agreements that were reached in the speech phase in the last legislature and also adds two aspects that were part of the clash that broke the negotiations. For example, objective what were previously considered respect for that they now refer to “insults or insults” that are not a crime.

In addition, the disobedience to the agents will go from a serious to slight infraction and a criterion is added so that it is “clear, clear and objective.” The PSOE has assumed with this writing a practically identical position that they defended during the past legislature EH Bildu and ERC. Of course, those points can be a clash in the coming months with the PNV, which has registered amendments to keep these offenses as serious.

Source: www.eldiario.es