It looks like we narrowly escaped.

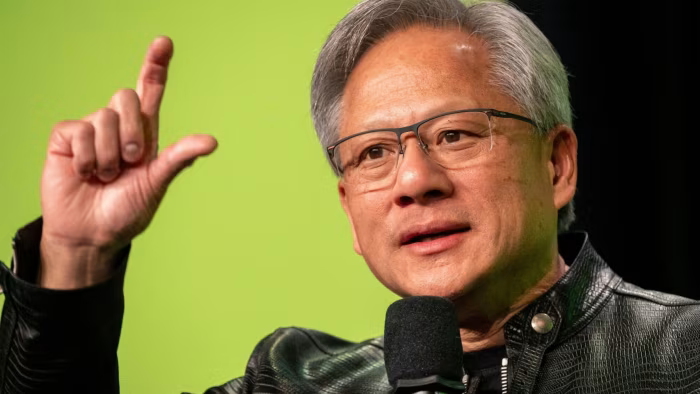

Nvidia is a $3.1 trillion company, and its stock has gained 800% in two years. It represents 6% of the S&P 500, which understates its symbolic importance as a centerpiece of the AI business. Consensus estimates for its quarterly earnings, released yesterday afternoon, called for a 115% increase in revenue. That understates what the market was actually expecting—probably by a lot. Based on (high) expectations for next year’s earnings, the stock is trading at a premium of about a third to the market. All of this is quite worrying from a market stability perspective.

Nvidia’s quarterly growth, however, was 120%, and the stock was down just 6% in late trading, not a catastrophic result. The rest of tech’s “Magnificent 7” stocks took the news in stride. Breathe a sigh of relief, everyone. It could have been a lot worse. We just need the market to stay calm today.

If it does—and it’s not guaranteed—the significance of this report could be that it puts the final seal on a major shift in market leadership. If 120% revenue growth isn’t enough to keep Nvidia’s stock steady, it’s hard to see how the company and its big peers can continue to lead the market as they have in recent years. Big Tech’s growth has been very good, but at current prices, good isn’t good enough. Unless growth picks up again, leadership may have to come from elsewhere.

The regime shift has been underway since Nvidia hit its peak on June 18. Since then, the technology sector has been a drag on the broader market, while sectors that benefit from falling interest rates, such as real estate, utilities and financials, as well as defensive sectors such as healthcare and consumer staples, have come out on top.

Mag 7 stocks have mostly underperformed the SPX since June 18. Only Tesla (which was down), Meta (relatively cheap) and Apple (which is a purely defensive stock at this point) have outperformed the index:

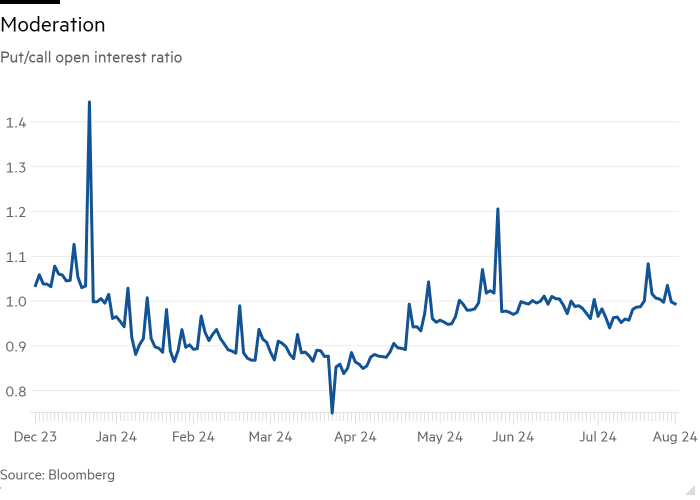

Options investors have noticed this shift. The put-call ratio, which had been tilted toward calls, has been balanced since June:

Regime change is probably healthy, as long as no one gets hurt in the transition. Overreliance on a single narrative can cause instability. However, it’s unclear which regime is replacing technology and AI. Small caps and value stocks have outperformed the S&P 500 since June, and the S&P equal-weight has outperformed the S&P. But growth stocks have lagged, dragged down by the technology sector:

We’re excited to see who comes out on top.

(Armstrong e Reiter)

‘‘Inflationary Greed’: The Big Questions

This week, I wrote a few articles about “greedflation.” I tried to focus on a specific corporate finance question: Did post-pandemic inflation provide a real profit boost for large food retailers, food brand manufacturers, and consumer goods companies? I tried to avoid economic and ethical questions, such as: How much of the post-pandemic inflation was caused by increased corporate profits? Were post-pandemic price increases unethical or something we should regulate?

When it comes to inflation, however, the big questions just won’t leave a guy alone. Isabella Weber, a renowned economist at the University of Massachusetts, shared a chart on X and some words from one of this week’s letters, and many people reposted it. Weber is the author of a famous paper arguing that “Covid-19 inflation in the U.S. is predominantly sellers’ inflation,” driven by coordinated price increases, and she also believes that price controls are a good policy response to economic shocks.

The reposts have sort of put me, at least on X, in the “greedflation is bad and should be regulated” camp. But I’m not in that camp. Here are some things I think we can say about the big issues, from a corporate finance and common sense perspective.

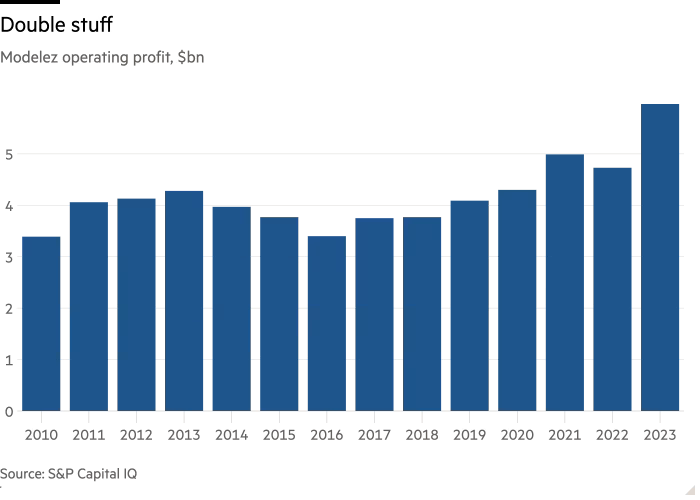

Some large companies in the food value chain have seen a large increase in nominal profits during the post-pandemic inflation, and this increase has been driven largely by price increases. Mondelez is a clear example here, as we noted yesterday. Here are the company’s operating profits over the past 13 years:

Mondelez’s 2021-23 years were extremely profitable, but its cookie and cracker sales grew only a few percentage points. There was no major improvement in costs. What happened was that a company that was growing in the low single digits went into double-digit growth because it raised prices, and much of that additional revenue turned into profit. And again, for the industry as a whole, this was not about margins, but about additional dollars of profit. Sales margins are a distraction from the “greedflation” discussion.

In real terms, the higher profit is a bit harder to interpret. In the 2021-23 period, Mondelez’s nominal operating profit was about 28% higher than in 2019 (which was already a good year). But CPI prices have risen about 20% since the pandemic began. And nobody questions a food company using price to keep its inflation-adjusted profits stable, right? Mondelez would probably have seen some profit growth even without inflation and price increases. So how much extra profit are we talking about here — and how much would be too much, if there is such a thing as “too much profit”? That’s not clear to me.

It’s important to know whether the price increases were possible because of excess demand or because of limited supply. If Mondelez was able to charge more because people had more money and were therefore willing to pay more for Oreos, that doesn’t seem like something we should regulate. But if there were cookie shortages because of the pandemic, that’s not so clear. I don’t know what the balance between supply shock and demand shock was in the food industry. But there’s an interesting nuance here. Yesterday, Francesco Franzoni from the University of Lugano sent me a paper he co-wrote. He argues that when supply chains are disrupted, large companies are less affected than smaller ones because they have more diversified supply chains and greater bargaining power (we’ve heard industry analysts make a similar point). This, Franzoni says, allows large companies to raise prices while gaining market share. Industry concentration can be inflationary in situations of supply shocks.

Another important question is whether these higher real profits, driven by prices, will be eliminated by competition. I can’t be too concerned about companies making extra money for a year or two after a major economic shock, if competition eventually normalizes economic relations. We seem to be seeing competition returning strongly, for example, in the fast food sector. If that doesn’t happen soon in the food sector, then there is something wrong with the structure of the market, which regulators should look into. But I don’t think we can conclude that competition has failed yet.

Por Robert Armstrong, via Financial Times.

Source: https://www.ocafezinho.com/2024/08/29/nvidia-sela-uma-mudanca-no-regime-de-mercado/