Arrival of the aircraft carrier Gerald Ford in the Caribbean reimagines the “America for the Americans” of the Monroe Doctrine two centuries later. History of pressures ranged from gunboat diplomacy to CIA operations.

Arriving in the Caribbean in mid-November, the American aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford carried with it two centuries of history of US pressure on Latin America.

The movement is no stranger to Latin American waters, which during this period saw countless military vessels set sail from the US to intervene in political crises, such as in Nicaragua, Haiti and Honduras, support coups d’état, as in Brazil, or project military force against governments considered undesirable by Washington, as in Cuba.

From the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 to Operation Southern Spear of 2025, the American interventionist stance changed its appearance. Before, the so-called gunboat diplomacy sought to make it clear that a war could be triggered by the slightest gesture of resistance. The tour of the American ships had a clear purpose: to provoke and intimidate targets within range of their cannons.

Today, the deployment of the aircraft carrier – and thousands of soldiers on board – takes place in a gray zone, in which traditional naval power is incorporated into a broader mix of tools, recalls historian Stefan Rinke, from the Latin American Institute at the Free University of Berlin. This is a more indirect and legally framed form of pressure.

“The United States increasingly frames its deployments as combating drugs, organized crime, terrorism and protecting maritime routes, combining these operations with sanctions, financial pressure, diplomatic isolation and information campaigns that delegitimize adversary regimes, such as Venezuela,” says Rinke.

In addition to deploying naval forces, the US carries out military exercises in Panama | Martin Bernetti/AFP/Getty Images

It is no coincidence that when the USS Gerald R. Ford arrived in the region, Washington had already hit 20 vessels in the Caribbean, causing more than 70 deaths under the justification of combating drug trafficking in recent weeks. The missile attacks occurred without the aircraft carrier being needed. His arrival, therefore, is interpreted as a political gesture displayed amid the unprecedented escalation of tension with Venezuela.

“It sends a message to Caracas and the rest of the region: that the United States, once again, is willing to use the full power of its military force to ensure that its will prevails across the continent,” says Elizabeth Dickinson, senior analyst at Crisis Group, based in Colombia.

The revamped Monroe Doctrine

Although recent, the approach dates back to the various tools of American power employed in the region over time. By advancing on the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the Panama Canal, Donald Trump renews the idea of “America for the Americans”, a famous synthesis of the Monroe Doctrine that guided the foreign policy of American President James Monroe (1817-1825).

In the 19th century, however, Monroe’s announced goal was to liberate the continent from Europe. Now, according to US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, the declared danger is China. In an interview in April, he said that Washington will recover its “backyard”, Latin America, from Beijing’s influence.

“It’s a moment of a kind of rediscovery of the region itself. And I think this is an interesting way of thinking about the various versions of US policy towards Latin America, ranging from the Monroe Doctrine – which specifically stipulated that the US would be the great power in this part of the world – to more covert and other types of operations over the last century”, says Elizabeth Dickinson.

USS Forrestal aircraft carrier was used to support coup d’état in Brazil in 1964 | US Navy

USS Forrestal aircraft carrier was used to support coup d’état in Brazil in 1964 | US Navy

From Banana Wars to Good Neighbor Policy

Over these two centuries, these episodes have taken many forms, ranging from intelligence operations to the use of ground troops. The starting point was set in 1823 by Monroe’s foreign policy, whose government began to see the Caribbean from a strategic point of view.

In 1898, with the Spanish-American war, the perspective of “Latin America seen from above” was put into practice in a more incisive way. The US victory in the conflict forced Spain to renounce its claims on Cuba and cede Puerto Rico’s sovereignty to the Americans. The victory gave Washington prestige. According to the US State Department, the war “consolidated the United States’ position as a power in the Pacific.”

A wave of occupations and military interventions was launched to control Caribbean governments and maritime routes, which lasted until 1934 and affected countries such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Honduras.

In the period that became known as the “Banana War”, Americans began to control customs, national banks and entire governments under the pretext of guaranteeing payment of foreign debts and protecting American companies, such as the United Fruit Company. Deadly battles against insurgents have been recorded in several protectorates. To this end, the use of naval forces became so common that, at the end of the period, the American Navy launched its own “Small Wars Manual”, which states that the conflict is not only military, but also social and political.

Pressure for Panama’s “independence” gave the US control of the Panama Canal | Heritage Images/picture alliance

Pressure for Panama’s “independence” gave the US control of the Panama Canal | Heritage Images/picture alliance

Such actions had strong roots in the so-called Roosevelt Corollary, a revision of the Monroe Doctrine launched in 1904 by Republican president Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909). The objective was to justify the intervention. In a historic speech to Congress, he denied that the US was “land hungry”. “All this country wants is to see neighboring countries stable, orderly and prosperous,” he said, but the “general loosening of the bonds of civilized society” could force the United States, “however reluctantly,” to exercise an “international police power.”

Roosevelt often recalled the advice to “speak softly and carry a big club” in his hands. In 1903, when he was already heading the White House, he applied this logic when sponsoring the separation of Panama from Colombia. American military ships docked in Panamanian ports to ensure secession. The new independent country was thus born under American tutelage, and saw US troops intervene in its territory dozens of times in the following years.

Cold War and covert operations

In 1933, another American president, Franklin Roosevelt (1933-1945), took power and launched the Good Neighbor Policy, putting a formal end to gunboat diplomacy and renouncing direct occupation. Operations in the region gained the status of logistical support and patrolling, with Washington establishing advanced bases in Latin American countries, such as Brazil, during the Second World War.

During the Cold War, naval assets were redirected to contain communism, offering support and cover for coups, blockades and counterinsurgency actions, explains historian Stefan Rinke. The well-known peak occurred in 1962, during the Missile Crisis, when the US formed a quarantine of ships around Cuba as a show of force in the face of the Russian nuclear threat in the region.

Covert operations by the American intelligence agency, the CIA, were also distributed in Latin America, launching coups d’état in Guatemala and Chile.

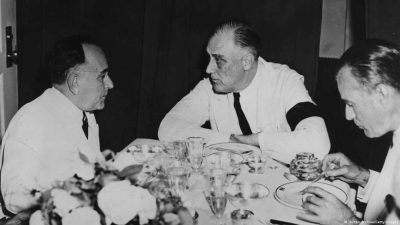

Getúlio Vargas (left) talks to Franklin Roosevelt aboard an American destroyer docked in Natal. USA implemented advanced bases during World War II | Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Getúlio Vargas (left) talks to Franklin Roosevelt aboard an American destroyer docked in Natal. USA implemented advanced bases during World War II | Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Brazil was also the target of one of these actions, albeit “silent”. In the so-called Brother Sam, the US sent its most modern aircraft carrier at the time, the USS Forrestal, to support the 1964 coup and enforce deterrence. As there was no resistance, the American naval apparatus did not arrive in the country.

US returns to patrol the Caribbean

“The end of the Cold War shifted the focus from direct regime change to markets, democratization and, above all, the fight against drugs, with naval power focusing more on patrols, interdiction and security cooperation,” says Rinke.

A new inflection was created with the new model: the reactivation of the American Fourth Fleet, in 2008, to patrol the seas of Latin America. The news was poorly received by leaders from different political spectrums in Brazil and Mercosur.

“Latin American governments noticed renewed US naval activism in the South Atlantic and the Caribbean, just when offshore resources and center-left governments were gaining importance”, points out Rinke.

In response to the criticism, five years later, Barack Obama’s Secretary of State, John Kerry, told the Organization of American States (OAS) that the “era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.” In the case of drug trafficking, the objective became to intercept vessels and judge their crew within due legal process, and the US promoted cooperation agreements with countries in the region.

Missile crisis marked the culmination of American policy towards the region during the Cold War | picture-alliance/Everett Collection/CPL Archives

Missile crisis marked the culmination of American policy towards the region during the Cold War | picture-alliance/Everett Collection/CPL Archives

“The relationship is not about a declaration about how and when we will intervene in the affairs of other American states. It is about all of our countries seeing each other as equals, sharing responsibilities, cooperating on security issues and respecting each other,” Kerry said at the time.

The proposal did not last long, as the new Trump administration reimagined Monroe’s “America for Americans”, in what was dubbed by the New York Post as the “Donroe Doctrine”.

The so-called Operation Southern Spear positioned 8% of its war fleet in the Caribbean, in addition to destroyers, fighters, drones, assault groups and a nuclear-powered submarine. The attacks on vessels that left dozens of people dead, recalls Elizabeth Dickinson, are carried out under intense technological apparatus. A new pressure formula was instituted.

For Crisis Group’s Dickinson, the magnitude of the new American mobilization caused a shock throughout the region. “We are at a moment of maximum pressure. This is a type of deployment and a visible American military presence that the region has not seen for a few decades, since it escaped many of the military dictatorships established in the 1970s and 1980s”, he argues.

Use of technology to target alleged drug traffickers marks a new era of American pressure in the Caribbean seas | Donald Trump/Truth Social/REUTERS

Use of technology to target alleged drug traffickers marks a new era of American pressure in the Caribbean seas | Donald Trump/Truth Social/REUTERS

New security logic in AL

The new logic differs from a maritime hybrid war, but its result is similar: “The use of naval platforms and legal narratives to coerce and shape behavior, without crossing the threshold of a formal war and keeping the option of escalation open”, adds Stefan Rinke.

For the researcher, this reinforces Latin America’s status as a distinct security space, subordinate to American power and increasingly contested.

“The Fourth Fleet and episodic aircraft carrier deployments ‘recentralize’ the Caribbean and the South Atlantic as militarized spaces, leading regional actors – especially Brazil and other South American middle powers – to articulate their own visions of security in the South Atlantic and to revive norms of non-intervention,” he says.

Such practices mean that non-traditional threats, that is, non-militarized threats, such as drugs, illegal fishing and migration, are treated as a military problem.

“At the same time, governments that perceive themselves as targets (Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua) interpret US naval movements as existential threats, reinforcing authoritarian tendencies, drawing closer to extra-hemispheric partners such as Russia, Iran and China, and intensifying ideological divisions within the regional complex.”

The result, Rinke argues, is a more fragmented and distrustful security environment, with the US naval presence both stabilizing and destabilizing the regional order.

Originally published by DW on 11/27/2025

By Gustavo Queiroz

Source: https://www.ocafezinho.com/2025/11/29/de-monroe-a-trump-como-eua-pressionam-a-america-latina/