That abortions were carried out mostly in the public health network and their referral to the private one was an exception. This is the objective proposed by the abortion reform in force since March 2023 to try to change the prevailing model in Spain, which prioritizes the performance of voluntary terminations of pregnancy (IVE) in concerted clinics. However, in light of the latest data, the norm has not managed, for the moment, to promote a significant change: 81.45% of abortions were performed last year in private centers, which represents a drop of only one point compared to 2022.

This implies that, although IVE is a health benefit included in the service portfolio since 2010, it is still not normally assumed by public health. It is something that has happened since the right was decriminalized in 1985 – although only in three cases – and, in general, it implies that women begin the process in their public reference center, but later, for the intervention itself, they are referred to clinics with which the Administration arranges the service and the users do not pay for it. Only 18.5% of them remained in the public circuit in 2023.

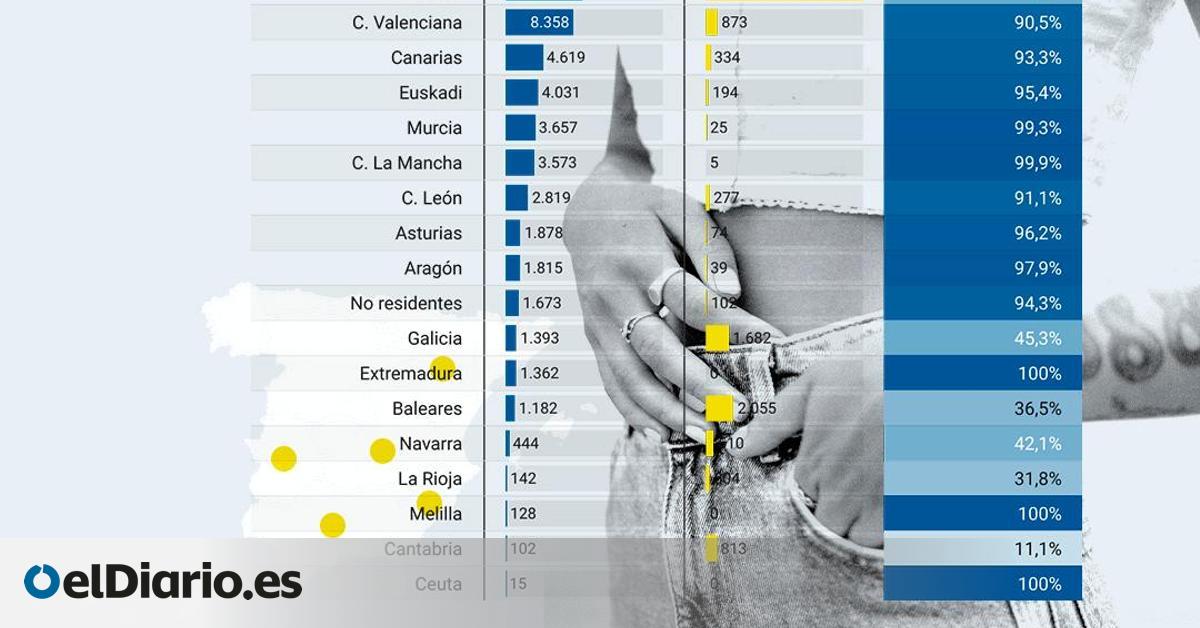

The situation is worse in communities where the number of abortions carried out in public centers is minimal. In some they do not even reach 50, despite the fact that they perform thousands of interventions a year. It occurs in Andalusia – where almost 20,000 abortions were performed in 2023 and only 26 in the public – or Castilla-La Mancha (five in the public compared to 3,573 in total). The same thing happens in Murcia, which only recorded 25 interventions out of 3,657, and Aragón (of the 1,815 abortions, only 39).

The situation is extreme in Extremadura, Ceuta and Melilla, which did not have a single abortion in public throughout the year. Furthermore, there are two communities in which the figure does not reach one hundred: Madrid (71 of 17,800 interruptions) and Asturias (74 of 1,878).

For Gema Fernández, a lawyer for Women’s Link, the data reflects “everything that still needs to be done” to comply with the law: “The ten months of 2023 that have been in force should be more noticeable in the figures if there was political will to change things.” The rule stipulates that the service “will be provided in centers of the public health network” and will only be referred to “exceptionally” concerted ones. “The law is clear, what cannot be is that we live in a permanent exceptionality,” says the expert.

The number of private abortions has been progressively decreasing. Thus, these have gone from constituting almost the entirety (they were 98.2% in 2010, the year of approval of the deadline law) to 81.45% in 2023. The decrease – and therefore, the consequent increase in interruptions in public centers – has been occurring steadily, around one percentage point each year, a trend that has also been replicated last year, now with the new abortion rule in force.

“In practice, there continue to be 17 models of abortion care and, in most cases, the law is not being followed or its implementation is being followed up. Work is being done in some places to be able to improve, but they are punctual and at the will of specific teams,” summarizes Silvia Aldavert, coordinator of the Association for Sexual and Reproductive Rights.

And the records of objectors?

To try to guarantee the change of model, the reform proposed to regulate conscientious objection through the creation of registries of objectors. The idea is to record on paper the number of professionals who refuse to perform abortions for ideological reasons in each community with the aim that the services can be organized to provide the service. In practice, it is a way to prevent health departments or entire hospitals from hiding behind a generalized conscientious objection to not undertake abortions in public.

Communities such as La Rioja, Murcia, the Canary Islands, Cantabria or the Valencian Community already have their records created; Castilla-La Mancha is working on it and others like Galicia or Navarra are waiting for the Ministry of Health to also do its part and finalize the protocol with the “minimum conditions” that these registries must integrate, as established by law. Just this week, Minister Mónica García announced that she already has a draft on the table and that “before the end of the year” she will take it to the Interterritorial Health Council.

On the other hand, there are the communities, with Madrid at the head, that not only have not put their registration in motion but are boycotting the measure. President Isabel Díaz-Ayuso was already opposed at the time and this week the Minister of Health, Fátima Matute, has expressed herself along the same lines and has accused Health of using the registry “as a political battering ram”: “Why is there Should you make a list of objectors and not those who do provide that service? What is the purpose of that, pointing?” he stated.

The more public, the more pharmacological

The new law establishes that centers must provide the two methods that currently exist to carry out voluntary terminations of pregnancy: surgical and pharmacological, for which only pills are used. The vast majority of women abort with the first technique, chosen by 70% in 2023, although the percentage has been progressively decreasing from 90% in 2011.

The distribution, however, is very different depending on the ownership of the centers: while in the public ones the pharmacological one prevails, in the subsidized clinics, the majority are instrumental. In fact, in recent years a parallel phenomenon has occurred: as the public has assumed more and more abortions, the number of pharmacological abortions has increased. And it is something that is clearly seen in the case of some communities such as Cantabria, La Rioja or the Balearic Islands, which perform many more abortions in public than the rest, but the majority with pills.

It is the way in which public health seems to be increasing the proportion of interventions it carries out, a path that sparks debate among associations, professionals and experts. There are those who are aware that the situation is not ideal and know that centers should offer both techniques, but they consider it “a first step.” Other voices suggest that, in practice, “the right to choose the method to which the law points is being sacrificed.” It is not that women cannot choose to have a surgical abortion, but there are cases in which, if they do, they are referred to private clinics even outside their provinces.

In this province no

A paradigmatic example is that of La Rioja, one of the communities that until recently did not make any intervention. However, the launch of a sexual and reproductive health care center settled the outstanding debt and Rioja women began to be able to abort, although only through the pharmacological method. If they choose the instruments, they are forced to travel abroad, specifically to a clinic in Pamplona.

For Aldavert, this is an example of how “with the current structures of the public health system” women “are not being able to choose on equal terms” in many places. “It is not about opposing the method per se, at all, but it is true that it is cheaper and easier and also the one that has the least implications at the level of conscientious objection of professionals,” he states, slipping that there would be those who would be willing. to dispense the pills, but not to intervene surgically in an abortion.

The Rioja women who want to terminate their pregnancy in an operating room are not the only ones who have to travel to exercise their right. Despite the fact that following a complaint from a woman defended by Women’s Link, the Constitutional Court ruled a year ago that forcing a woman to travel violates her fundamental rights, it continues to be done. In fact, there are 12 provinces that have not reported interventions in 2023, but there are women who have undergone them. As? Being referred to other places. They are Jaén, Huesca, Teruel, Toledo, Guadalajara and Cuenca in Castilla La-Mancha, Cáceres and Ávila, Segovia, Soria, Palencia and Zamora in Castilla y León.

This occurs because in these provinces the public system does not provide abortions, but there are no private clinics with which to arrange services. “It is something very serious that this continues to happen and even more so after the Constitutional ruling. It is a violation of rights, but it also has first-hand implications for the women themselves. You have to keep in mind that to move you will have to ask for permission from work, have some family support and even want to tell them. And maybe it is something that not everyone wants or can afford,” says Fernández.

Source: www.eldiario.es