European Commission plan calls for reliable semiconductors in drones

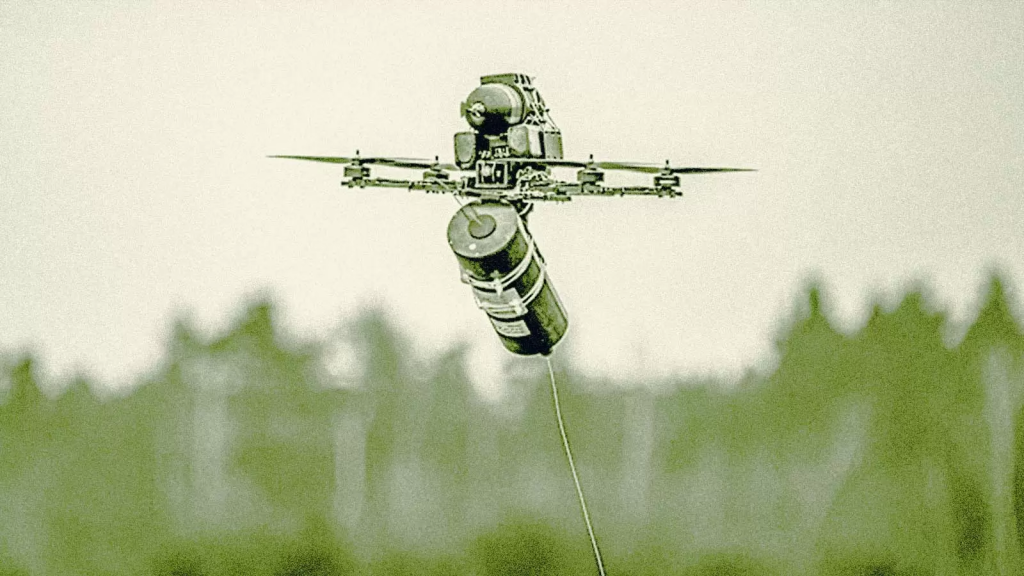

While scenes of drones modified for war dominate international news, a different but equally crucial battle begins to unfold in the corridors of Brussels. This is a race for technological sovereignty, where the most valuable piece is not the drone itself, but the tiny brain that controls it: the semiconductor. The European Union is preparing a bold move to regain control over its skies and its production chain, proposing the mandatory use of “reliable semiconductors” in all civil and defense drone systems manufactured in the bloc.

The measure is the core of a new comprehensive strategy that the European Commission is expected to reveal in the coming days. The plan does not emerge from a vacuum. It is, above all, a direct response to an increasingly tense and fragmented geopolitical reality. The dependence on electronic components manufactured outside the continent, especially in regions of instability or under the influence of strategic rivals, has become an unacceptable Achilles heel.

Also read: Why does the EU want to change civil and military drone policy?

The trigger for the acceleration of this project was loud and undeniable. In September last year, the silence of the night over Poland was broken by the trail of NATO fighters on an interception mission. The target: 19 Russian drones that violated the alliance member country’s airspace. The episode wasn’t just another raid; It marked the first time since the start of the large-scale invasion of Ukraine that a NATO country shot down a military aircraft on its own territory.

This event acted as a reality check. He showed, dramatically, that the drone threat transcends conventional battlefields and can penetrate directly into the heart of Europe. The vulnerability was exposed. More than unmanned planes, what crossed the border was a clear message about the ease with which collective security can be tested by accessible and ubiquitous technologies.

Given this scenario, the European drone strategy ceases to be a technical document and becomes a matter of collective national security and the preservation of the European social model. The bias, therefore, is clear: strengthen internal industry, generate high-quality jobs on European soil and reduce dependence on external powers. It is a pragmatic leftist stance, which sees strategic autonomy not as a warmongering project, but as an imperative for peace and social stability.

But what ultimately defines a “reliable semiconductor”? The proposal goes far beyond the simple quality of the component. The focus is on three fundamental pillars: safety, resistance and traceability. These chips will need to be designed and manufactured to standards that guarantee their immunity to cyberattacks, physical tampering or the inclusion of “backdoors” – intentional flaws that could allow remote control by hostile actors.

The idea is that, from the package delivery drone to the border surveillance vehicle, each integrated circuit has a kind of digital, tamper-proof “certificate of origin”. This implies a massive investment not only in factories (so-called “foundries”), but in the entire research, design and certification ecosystem. Europe intends to create its own standard, a guarantee seal that will be a condition for operating in its internal market.

This movement is complemented by other practical initiatives that the strategy must detail. Among them, the acceleration of the anti-drone alliance with Ukraine stands out, a partnership that, announced some time ago, is now gaining maximum urgency. The Ukrainians’ real-time warfare experience combating Russian drones is an invaluable laboratory, and the EU wants to integrate this knowledge into its defense industry.

To turn the plan into reality, Brussels is betting on an unprecedented mobilization of the private sector. Before the summer, the Commission will convene an industrial forum bringing together electronics giants, drone startups, research centers and representatives of Member States. The objective is clear: map capabilities, identify bottlenecks and align investments to scale production at war speed.

The timeline is ambitious and reflects the perceived urgency. The goal is to establish a research and development center dedicated exclusively to anti-drone defense by the beginning of 2027. At the same time, this fall, the bloc intends to create rapid response teams for emergencies involving drones. These units, made up of experts from several countries, will be ready to move to any point in European territory where a threat of this kind is identified, reinforcing operational cooperation.

Internal coordination will also be strengthened. Each member country will be asked to appoint a national coordinator for drone safety. These officers will be the links between Brussels policies and implementation at national level, monitoring the action plan and ensuring the fluid exchange of information. Significantly, the plan will remain open to close partners such as the UK and Norway, recognizing that technological security is a transnational challenge.

The strategy, however, was not born under total consensus. The idea of a “anti-drone barrier” – a concept of a continuous electronic shield at borders – had already been raised last year and received with reservations by some governments, who questioned its cost, technical feasibility and environmental impact. The new plan appears to take a more pragmatic approach, focused on resilience and response, but debates over budget and shared sovereignty promise to be heated.

Furthermore, the advance of 6 billion euros from a G7 loan for the alliance with Ukraine signals the priority of the issue, but also highlights the pressure on public coffers at a time of multiple crises. Supporters of the plan, however, argue that the cost of inaction is infinitely greater. They see every unreliable drone in European skies not just as a security risk, but as a high-tech job that was no longer created on European soil.

The European Union’s bet, in short, is one: reconnecting its technological destiny to its political project. By prioritizing the “reliable semiconductors”the bloc is not just protecting its airspace; is deliberately building the foundations for a sovereign industry, capable of sustaining its social welfare model in an increasingly contested world. The battle for the future, planners in Brussels demonstrate, is no longer fought just in the field or at sea, but in lines of code and nanometric silicon architectures that are now literally commanding the skies.

Source: https://www.ocafezinho.com/2026/02/09/europa-aposta-em-chips/