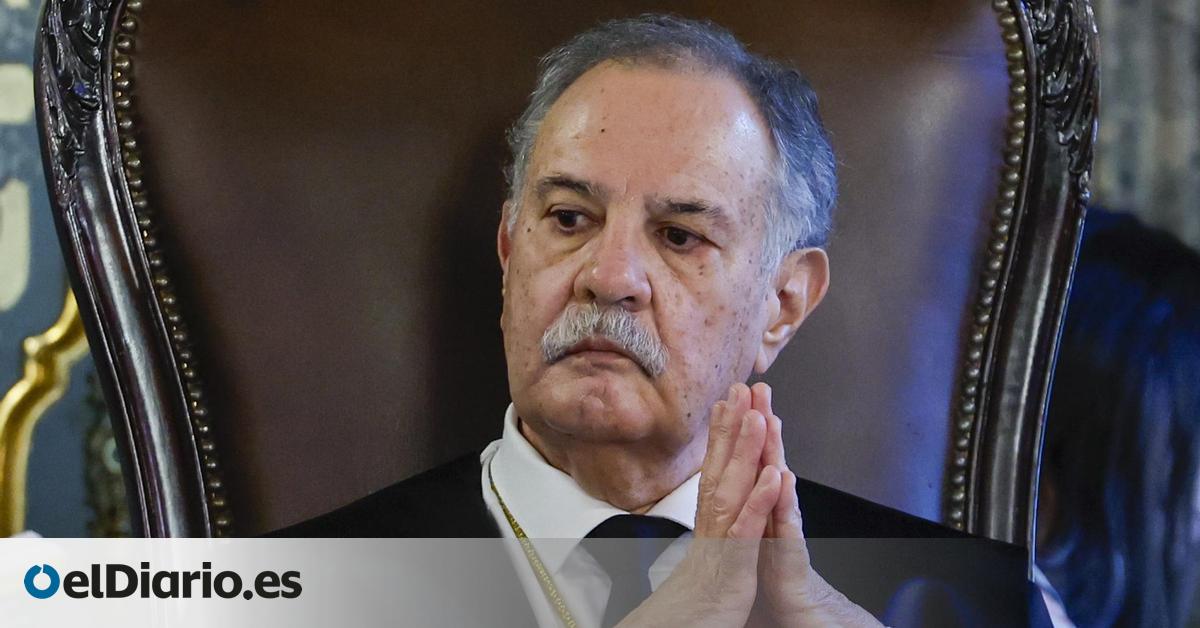

The Supreme Court ruling that convicted Álvaro García Ortiz has not only put an end to his career as attorney general and has made him responsible for the leak of the confession of tax fraud by Isabel Díaz Ayuso’s partner. It also represents a boost to some of the most controversial points of the investigation: the records and deductions of the Central Operational Unit (UCO), the orders of Judge Ángel Hurtado to collect messages and telephone data from García Ortiz and the decision to judge only the then attorney general although the final sentence points to his “environment”, which appeared in the Supreme Court almost in its entirety.

It has been one of the points that have consecrated the unprecedented nature of the process, trial and conviction of the attorney general. The direct confrontation of the Prosecutor’s Office and the State Attorney’s Office with a Supreme Court judge and the Civil Guard unit in charge of numerous corruption cases. The criticisms of the Public Ministry and the defense of García Ortiz began with the opening of proceedings in the Superior Court of Madrid, were established in the Supreme Court both in the investigation and during the trial and have been rejected by the sentence with the next goal in the Constitutional Court.

The most open and direct confrontation with Hurtado came from the attorney general himself when he sat before the judge to testify as a defendant last January. “The investigating magistrate has a certainty that does not lead us to the discovery of the truth,” said García Ortiz. The State Attorney, Consuelo Castro, developed the complaint in the first trial session: “He has been subjected to an unfair process as a whole,” she criticized before describing Hurtado’s investigation and her “preconceived” idea that García Ortiz was the culprit as “prospective” and “inquisitorial.”

The darts have also flown towards the UCO, before and after the testimony of Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Balas became one of the most valuable weapons of the accusations. From the first complaints about the searches ordered by Hurtado to the complaints of bias because his key reports cut messages and omitted, among other things, the Miguel Ángel Rodríguez hoax. Each and every one of these complaints – which in a few weeks will be in the hands of the Constitutional Court – have been rejected by the Supreme Court.

From the UCO registry to leaks

The judges of the Criminal Court only make two small concessions to García Ortiz’s complaints without any consequences. The first, when they recognize that Ángel Hurtado was imprecise when ordering the first searches of the Civil Guard and the seizure of messages and emails from both the attorney general and the other defendant, the provincial prosecutor of Madrid. “The time limit initially set could actually be disproportionate: it exceeded what was strictly and prudentially necessary,” the judges concede. But this possible trawling entrusted to the UCO by Hurtado, they immediately add, “has turned out to be totally irrelevant.”

It was one of the first resources in the case. When the Prosecutor’s Office and the Law Office reported that Hurtado had authorized the UCO to seize emails and messages from March to October 2024. The judge took note and, in a subsequent resolution, temporarily limited the diligence to the days of the leak. “It limits the analysis and examination to the messages and content produced on those strict dates,” the ruling supports.

The Supreme Court also sees no irregularity in the management that the judge and the UCO itself made of all of García Ortiz’s telephone information that they collected and that, after being transferred to the parties, was leaked, with the then attorney general and his collaborators receiving unwanted emails and calls. The registry, say the judges, was “an absolutely appropriate measure” and the leaking of the attorney general’s data is not Hurtado’s responsibility either: “If the data thus transferred to all parties, accusations, the Prosecutor’s Office and defense, ended up being known by the general public, the instructor cannot be attributed an act of transfer or improper access to such data by third parties unrelated to the case.”

The Central Operational Unit (UCO) of the Civil Guard was in charge of carrying out Hurtado’s proceedings from the very opening of the case, but then his name and that of Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Balas, instructor of the key reports and records of the case, were not in the headlines: public opinion did not know then, for example, that the former socialist militant Leire Díez was seeking information about the unit and its person in charge to, supposedly, discredit its role in corruption cases that affect the PSOE and the Government.

The expression that Balas – in a public trial as tense as his previous statement behind closed doors in the investigation – used to talk about the “control of the fact” that García Ortiz had over the leak is not reflected in the sentence, but the same argument that leads the judges to condemn is. And in their sentence, as Hurtado already did during the investigation, the judges of the Criminal Chamber make a closed defense of the role of the UCO in the case and the management of the seized material.

“We cannot cast suspicion on the agents that they have been able to clandestinely copy that information for unknown purposes for spurious purposes,” says the Supreme Court to endorse the records. “The fact that police agents had a copy of the data collected does not allow us to suspect that this allowed them to analyze that data without any control,” they add. “It must be presumed in principle (which does not prevent it from being possible to demonstrate that bankruptcies have occurred) that the actions of the agents have complied with what was ordered.”

From the note to the attorney general’s “environment”

Not all Supreme Court justices have signed this general endorsement of the sentence against Hurtado and the UCO. The dissenting judges, Susana Polo and Ana Ferrer, understand that Hurtado did not correctly assess that the telephone number he was searching, at first with few time limits, was that of an attorney general: “It was about confirming a suspicion about the leaking of an email that, as a great secret, contained the proposal for a conformity pact, which had already been publicly disseminated, and strategically distorted from the environment of the affected person.”

These two judges understand that there is no evidence that allows the leak to be attributed to García Ortiz or his “environment”, and they also dispute that the press release that the Prosecutor’s Office issued in March 2024 to combat hoaxes in the case is an improper disclosure of confidential data. One of them, Susana Polo, was in fact the rapporteur of the order who agreed to open the case but rejecting that this note could become a crime.

The Court endorses this change of direction that Hurtado announced verbally before García Ortiz’s statement in investigation and that now constitutes a main pillar of his disqualification sentence. And he rejects something that the former attorney general denounces from the beginning: that Hurtado only considered the possibility that he was most responsible for the leak. “There were several people investigated and the process, in an orderly and gradual manner, has been advancing” until the trial, justifies the Supreme Court.

The judges allude to the accusations that were filed, although not always at the request of Hurtado: the prosecutor Julián Salto and the commanders of the Prosecutor’s Office Diego Villafañe and Pilar Rodríguez. The first was exonerated by the Superior Court of Madrid, the second by Hurtado and the third by the Appeals Chamber of the Supreme Court. Which connects with the central axis of the sentence: the “environment” of the attorney general.

The ruling declares it proven that either García Ortiz or his “environment”, with the consent of the former, leaked González Amador’s email to Cadena SER on the night of March 13, 2024. The judges do not explain who that “environment” is but they do speak of a “small number of people in the defendant’s immediate environment” who knew him. Julián Salto, Pilar Rodríguez, Almudena Lastra, Álvaro García Ortiz “and his environment” and the lawyer Carlos Neira.

These were, according to the Supreme Court, the “potential insiders” of the case opened against González Amador and his written confession of tax fraud. The list made by the judges serves to rule out, they say, that many more people had access to that email because it had arrived in a generic mailbox of the Madrid Prosecutor’s Office a month before its leak, and is faced with a fact: all of these people have testified, some as witnesses and others accused several times, throughout the case. And others who learned the information about the possible pact that night have not even been called to appear in a year and a half of investigation.

Source: www.eldiario.es